Interview with Albert Steg about the Small-Gauge Erotic Film Collection

Administered by the Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies, the Sexual Representation Collection (SRC) is Canada’s largest collection of sex work history and adult film history. Thanks to the generosity of donor Albert Steg, a film archivist and private collector, the SRC has expanded its collections to include 1,500 8mm and 16mm film, including hundreds of stag films, pre-war hard-core films, and coin-op peepshow films. The SRC is currently working to process and make the collection available to scholars and community members worldwide. To celebrate this milestone, we interviewed Albert about the collection, including highlights from the collection, why he started the collection, challenges of collecting and preserving erotic materials, why he chose to donate his collection to the SRC, and what he hopes scholars and the public gain from the collection.

Q: As an archivist, you know that ‘unofficial’ materials related to sexuality, erotica, and adult film history exist in all kinds of libraries and archives, often set aside on out-of-the-way shelves, uncatalogued, ignored, and forgotten. Rarely do these materials receive the attention they deserve. As a result, historians face accurate challenges to writing histories of sexuality and pleasure. Tell us a little about when, how, and why you began to collect these materials. Did you have a particular focus on mind? Why is this collection important?

I began collecting films when I happened upon a little 8mm film at a flea market in around 1998. It was a Castle Films condensation of It Came From Outer Space, and I bought it mainly for the stylish box illustration. I managed to find a working projector that same day and pretty soon I was throwing cocktail parties with vintage movies projected on the wall mashed up with music in the manner of the old Wizard of Oz / Pink Floyd trick.

It was right around the time eBay emerged, and I soon discovered a whole vast bazaar of old films to pick from, especially once I stepped up to the more robust 16mm format. I became fascinated with all genres of “ephemeral films,” which are movies produced for some particular purpose, with a limited audience and a short intended lifespan. Think of television commercials, education films, industrial shorts pitching some new technology or social program. These are all genres that “date” themselves quite quickly, often to poignant or hilarious or shocking effect. Aesthetic styles (clothing, hair, consumer goods) and social values (manners, morals, values) that are almost invisible at the time of production will induce howls, sighs and gasps viewed at a few decades’ distance. Soon I expanded my private parties into a micro-cinema series at a local art gallery, where I would put together thematic programs of short films.

One weekend, back at the same old flea market, I spotted a shoebox full of 8mm films and asked what they were. “Stag films.” He hauled them out and I saw they had some hand-written labels and titles on them indicating they were from the 1950’s. When I got them home, I was stunned to find not just the expected Playboy-level brand of nude films, but some highly explicit hardcore sex films as well. There were porno movies in the 50’s? I hadn’t really thought about it before, but I had always vaguely imagined an unbroken line of sexual expression from Victorian prudery to 1970’s libertinism, and these seemed to have jumped the queue by a good twenty years. Were they even legal? So stag/erotic films became another of the ephemeral small gauge film genres I collected.

Before long I made the acquaintance of like-minded people in the film preservation community, at first by attending the Summer Film Symposium at Northeast Historic Film in Bucksport Maine, and then the offbeat Orphan Film Symposium then being held in Columbia, South Carolina, and finally by attending the Selznick School of Film Preservation at George Eastman House in Rochester, NY. It was a perfect time to get involved, because by that point major archives like GEH and institutions like the Library of Congress had come around to the idea that “little” films – amateur productions, home movies, educationals etc. were important cultural artefacts worthy of attention and preservation.

In the archival community I found a number of people collecting in my areas of interest – Rick Prelinger (Prelinger Archives), Skip Elsheimer (AV Geeks), Stephen Parr (Oddball films) and many others were inspiring models for me, as were a circle of archivists who founded the Center for Home Movies, dedicated to preserving family films, another of my major interests. I joined the board of CHM and served on it for a happy decade. Over the course of this time, I found that stag / erotic films was the one genre I collected that wasn’t already being covered by others in the milieu, so I gradually became the guy who knows a lot about stag films.

Q: What challenges did you face in collecting and preserving these materials?

The biggest challenge is probably the thing that made collecting the material so interesting: the lack of any existing collector’s guides or lists or histories. There’s one mode of collecting behavior (baseball cards, comic books) where there are known series of items, arranged by year or number or participant, and the fun is in completing the runs and getting the best specimens you can of each item in your field of interest. You can take a similar approach in collecting, say cartoon animation (you might be a Fleischer guy, like me, or a Disney or a Looney Tunes aficionado) or even educational films, where there are known studios or distributors (Coronet, Pyramid) or infamous titles to track down.

The milieu of erotic / stag film production from say 1900 – 1970 was almost completely uncharted, so collecting in this situation is a process of gradual discovery, and of understanding new discoveries by placing them in relation to what you already know, building out the broader context of the field as you go. Typically I would acquire a box lot of films someone had discovered in their father’s attic or garage and then work through them, see what there was to see. This is I think what every collector enjoys most – acquiring a neglected cache of potentially interesting or valuable but unknown material. So one day you turn up a film shot at a nudist camp for the first time and that’s something new that adds to the overall picture. Or you find a film featuring a familiar or known model like Betty Page, or you recognize a location or title card style you’ve seen before and gradually you map out the territory based on what you find.

A substantial challenge for all film collectors is how to deal with volume and storage. Films are a lot bigger than baseball cards, and it’s not hard to become overwhelmed. As small gauge (8mm and 16mm) films were superseded by newer media, libraries, families, and even collectors inevitably started discarding old films in quantity. Many collectors eagerly acquire large inventories of material when they can, often renting storage as cheaply as they can to hold it all. That can be a very selfless thing to do, prolonging the life of artifacts that might otherwise end up in landfill – but the financial burden can be substantial and collectors often find they have nowhere to deposit the films at the end of their career and the landfill beckons once more.

Early on I made a rule for myself that I would be selective in my collecting, retaining only a fraction of the reels I acquired, and that I wouldn’t amass more new films than I could reasonably expect to “get through” in a year or two. I limited myself to an 8×8 storage unit for holding both my permanent collection and unprocessed “inventory.”

The eBay phenomenon was essential to my collecting strategy. Early on I discovered that by buying films in batches whenever I could and selling most of them singly, I could make enough profit per-film to pay for the ones I kept for myself. So anytime I acquired a box lot of film (whatever the genre), I would do an immediate triage segregating the potential “keepers” or “good sellers” that I would take the time to screen, and immediately selling off the less promising titles in a lot sale, usually at a small loss but getting them out from underfoot. Films that were extensively damaged or decayed or moldy went straight in the trash unless they had some very compelling, unique content that argued for particular care.

My process worked well enough that the material I sold paid for the material I kept, paid for storage and supplies, and paid me enough annual income on top that I did report my film earnings along with other freelance work for tax purposes. This made it easier to donate my collection at the end of the day, since in a meaningful sense it was already “paid for.”

Q: What are some of the highlights of the collection and why? What items are particularly rare or unique? What items will be particularly valuable to scholars?

It is useful to distinguish two modes of erotic film production: the legal and the illicit. Those first hardcore films I found at the flea market were indeed illegal at the time they were created. The term “Stag Film” is often used to refer to any pornographic movie distributed on film media, but it more particularly refers to 16mm hardcore films, typically 400’ (about 13 mins) long, that were shown in all-male settings such as fraternities or lodges at events sometimes called “smokers” from the 1920’s (when the amateur-friendly 16mm film gauge was introduced) to the 1970’s when hardcore pornography was broadly legalized in the wake of Deep Throat. I use “Erotic Film” to refer to other, less explicit genres of stag film.

By immediate consequence of their illegality, the “illicit” category of films, particularly the early hardcore stag films are the most rare. They would have been printed in relatively small quantities as they were distributed to travelling showmen and “under the counter” smut peddlers, and would have been prey to various confiscatory authorities like the police. My donation includes around 140 of these titles. The ones produced in the 1920’s to early 30’s are I think particularly interesting because they tended to be relatively elaborate productions, often with “humorous” intertitles and a distinctive narrative element.

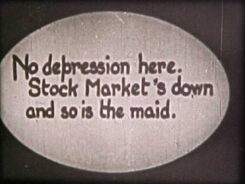

For instance, “The Hypnotist” (ca. 1930?) engages a familiar ethnic trope. A white couple visit the exotic Madame Cyprian, presumably for a séance or fortune-telling, but the action suggests something more like marriage counseling as the seer takes one and then the other in hand behind a curtain to impart sexual knowledge before joining both in a threesome. In what’s perhaps the first instance of a sex worker performing roles in multiple productions, the same actress appears in another stag, “The Golden Shower” (also ca. 1930) in which she plays a housemaid to a wealthy New York mistress (“Miss Park Avenue”). The “golden shower” is bestowed not, as erroneously suggested in one stag documentary, upon the woman of color, but on the wealthy lady of the house, by the butler. The three featured sex scenes engage taboos of ethnicity (black-white), class (employer-servant), and gender (woman-woman), all in under 11 minutes. There’s plenty for scholars and cultural critics to unpack there!

The intertitle pictured here helps to date the film to the aftermath of the market collapse in 1929. The film stock of the print I have donated dates to 1948, demonstrating that these early stag productions enjoyed repeated printing and distribution for many years.

Another genre of particular interest is the “Peepshow Loop,” again perhaps 400’ in length and printed in limited quantities as they were made for installation in coin-op machines in adult arcades, not mass-produced for home viewing. While this form of erotica was legal, the producers had to be careful to stay on the right side of censors, and since this form of exhibition thrived from the late 1940’s all the way into the 1970’s, these films encapsulate not just a history of lingerie and hairstyles, but of the limits of nude display and sexual activity.

The loops (so named because they were installed in machines for continuous display without rewinding) typically feature women in playful poses and relatively modest nudity, but in the 1960’s grow more explicit, progressing to couples in “softcore” contact, until near the end of the era we find unrestrained hardcore content. Something Weird Video in Seattle acquired and released 100’s of VHS compilation tapes of these films, but without any apparent attempt at organizing them, and some of the 250 or so loops in the collection I have donated, spanning 2+ decades, come from their eBay sales of the original materials.

The large quantity of approximately 600 8mm films likewise span a broad swath of porn production from the 1950’s – 1980’s, but this format tracks consumption of what was largely the legal and commercial forms of production. 8mm was the first moving-image format inexpensive and portable enough to be enjoyed by a mass audience of consumers. While there are some early hardcore films in this part of the collection that may have been illicit (because too explicit) at the time they were sold, most are titles that were available for mail order from the backs of men’s magazines or “adult bookstores.” The 8mm collection includes a large but not exhaustive overview of the popular hardcore series and performers who flourished in the post-Deep Throat era of permissiveness, including some of the controversial early films of Linda Lovelace before she achieved stardom, and many John Holmes appearances of the day.

With their numbered-series approach, commercial series such as Playmate, Swedish Erotica, Diamond Collection, Golden Girls, etc. do lend themselves to the collecting mode more akin to comic books, and while over time I attempted to complete as many entries as possible in my database, it wasn’t my aim to preserve physical prints of every film in every series, owing to the vastness of that task. Since these films were mass-produced they wouldn’t be considered the “rarest” of materials in the collection, though as I bought and sold many prints of most of these titles over time, I was able to retain an example in the best available condition for many, particularly with regard to color fading – and as time passes and 8mm projectors become fewer and fewer and acetate inevitably decays, a well-preserved collection such as this could be virtually all that survives of the genre.

Q: Historians of pleasure and sexuality face numerous archival and preservation challenges, including a lack of accessibility, perplexing metadata and filing protocols, the thin paper trail sex workers and sex industries leave behind, conservative institutional politics, the low priority that archivists sometimes attach to sexual histories, and financial barriers to research. What made you decide to donate your collection to the Bonham Centre’s Sexual Representation Collection at the University of Toronto?

To your list of challenges, I’d add that the general opprobrium surrounding the consumption of pornography, particularly in the small-gauge film era, meant that every time stag films were left behind by someone, there was a strong likelihood that the materials would be promptly destroyed by the people who found it – whether out of moral disapprobation or simply because they don’t want to think about grandpa’s erotic fantasy life.

There were a couple of institutions in the United States I had hoped might be interested in acquiring my collection, especially since it comes fully conserved and catalogued, relieving what can be a real burden for archives when they accept film donations. One university film archive was very keen on the acquisition, but the proposal was apparently blocked by the larger institutional decision makers. I think that the collection would have more easily found a home perhaps ten or 15 years ago, in a period when universities had pretty thoroughly embraced the validity of studying consumer culture and sexually-oriented behavior as academic fields, but before the ‘Me Too’ movement emerged, as well as a general atmosphere where students or pundits or various constituents are more inclined to publicly condemn materials like this along with the professional and moral judgment of the officials would allow it to be acquired. US institutions know that this is the kind of acquisition that is not likely to be met with general celebration or even indifference, and defending it might be tiresome at best.

It might seem strange, but I am perfectly happy for scholars or writers or documentarians to make use of this collection to build arguments that pornography is morally abhorrent or socially destructive. What I am not happy to see is destruction or disposal of cultural artifacts. I don’t mind people arguing that it would have been better if this stuff had never been made, but I do mind concluding that it should therefore be destroyed. I’m a collector-archivist, not a historian or cultural critic.

So, I was very happy to discover in the Bonham Center an institution whose mission clearly embraces the preservation of this collection, and whose mission has in turn been embraced by a large, established entity like the University of Toronto. That the university has such terrific archival resources that will allow ready access to the materials is an added surprise, as I am aware of how costly it can be to make moving images from film media widely viewable. So, whereas my hope was just to see the films survive beyond my stewardship of them, it looks like they’ll promptly realize the cultural function I had only imagined they might find at some vague future date.

Q: What do you hope scholars and the public gain from the collection?

Enduring access.

Albert Steg Manchester-by-the-Sea, 2022