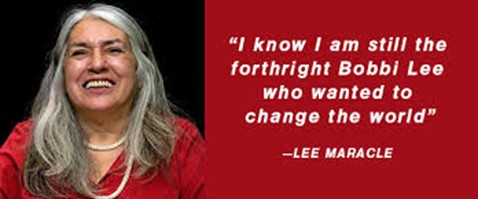

The Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies Remembers Lee Maracle

Students, faculty and staff at the Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies, along with so many others here at University of Toronto, and across the country, are deeply saddened by the passing of Lee Maracle on November 11, 2021 in Surrey, BC, age 71. A writer, teacher, mentor, feminist, and activist, Lee, born in North Vancouver, was a member of the Stó:lō Nation, with Salish, Cree and Métis heritage. At UofT, she was a member of the Elder’s Circle at First Nations House and an instructor for many years with the Indigenous Studies program.

A prolific writer and collaborator, Lee was the author of some 20 books of fiction, poetry and non-fiction, including essays, criticism and life-writing. In many of her works, she examined women’s lives, including her own, bringing to the fore the particular ways in which gender, racism and colonialism work as intersecting formations to create the unique structures and systems of vulnerability, marginalization, and discrimination, including sexual and physical violence, that Indigenous women have experienced. Cultivating a voice and finding a language to express those experiences and resist that silencing and victimization, her work also explores the connections between oral and written forms of storytelling and the reparative power of creative expression in works such as Bobbi Lee: Indian Rebel (1975; 1990); I Am Woman: A Native Perspective on Sociology and Feminism (1988; 1996); Sojourner’s Truth and Other Stories (1990); Ravensong (1993); First Wives Club: Coast Salish Style (2010);Celia’s Song (2014); Talking to the Diaspora (2015); Memory Serves: Oratories (ed. Smaro Kamboureli, 2015); My Conversations with Canadians (2017); and Hope Matters (with her daughters Columpa Bobb and Tania Carter, 2019). Her work also appeared in many anthologies including alongside Tomson Highway, Gregory Scofield, Daniel Heath Justice, and Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm in Drew Hayden Taylor’s Me Sexy: An Exploration of Native Sex and Sexuality (2008).

Lee Maracle held many positions in her long and diverse career: Cultural Director at the Centre for Indigenous Theatre in Toronto; founding member of the En’owkin International School of Writing in Penticton, BC; and teacher, visiting professor and writer-in-residence at many institutions, including Guelph University, University of Waterloo, Southern Oregon University, Western Washington University, and Kwantlen Polytechnic University in Surrey, BC.

Along with numerous nominations, Lee was the recipient of many honours and awards including Officer of the Order of Canada, the Premier’s Award for Excellence in the Arts, a Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal (for her work promoting writing among Indigenous youth), the Blue Metropolis Festival First Peoples Prize, the Harbourfront Festival Prize, and she was a 2020 finalist for the prestigious Neustadt International Prize for Literature. (Carrying a purse of $50K US and dubbed the “American Nobel,” its Canadian finalists have included Mavis Gallant, Alice Munro, Michael Ondaatje, Margaret Atwood and Ann-Marie MacDonald but which only two Canadians in its fifty-year history have won—Josef Škvorecký and Rohinton Mistry). In 2009, she received an Honorary Doctor of Letters from St. Thomas University in Fredericton, NB.

Lee was many things to many people, and her stature in the community and the esteem in which she was held by other Indigenous writers are a testament to her influence, her accomplishments and the great love and respect she engendered. Fellow authors have spoken about how her pioneering work helped to create and make space for a whole generation of writers who have come after her. Cherie Dimaline (author of the award-winning The Marrow Thieves) and Katherena Vermette (whose novel The Strangers just won the illustrious Atwood Gibson Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize) have paid tribute to the way Lee’s work made it possible for them to not only imagine themselves as writers but to see how writing itself had the power to build community by sharing stories about the history and experiences of Indigenous peoples in this country. Indeed many Two-Spirit and Indigenous LGBTQ+ writers, such as Gregory Scofield (award-winning poet of The Gathering: Stones for the Medicine Wheel; Love Medicine and One Song; Witness, I Am), Billy-Ray Belcourt (author of the Griffin Poetry Prize winning This Wound Is a World and the queer memoir, A History of My Brief Body) and Joshua Whitehead (whose novel Jonny Appleseed won Canada Reads 2021) have also acknowledged Lee’s mentorship and support when they were struggling to find their own voices and the spaces where they could be heard. Whitehead recalls one such gathering:

I asked a question about Two-Spirit stories and peoples and our relationship to publishing in our own Indigenous communities. It fell upon mostly deaf ears—a response I had normalized. Until Lee Maracle stood up, took my hand, and asked me to partake in her smudging ceremony. She loudly announced to the room, “This young one has asked all of us important questions that we cannot afford to not answer. We will not fail him. We will give him an answer by the end of the day, so get thinking, especially us elders.” I will never forget her raising me up, literally and metaphorically, into a space where I had a voice, where I could be [as] queer as I damn well pleased and that never took away from my Indigeneity (in fact they were symbiotic). She raised me into a space where I could partake in ceremony and community, and, in a way, she gifted me the rock I needed […] when it came to my own voice and confidence in my identity.”

In 2017, the year many across the country were celebrating “Canada 150,” the Bonham Centre Awards Gala, which honours those who have made a significant contribution to the advancement of and education about sexual diversity, chose to recognize the work and activism of four Indigenous and Two-Spirit leaders: artist Kent Monkman; comic, writer and broadcaster Candy Palmater; artist and activist Teddy Syrette; and Lee Maracle. Acknowledging the support and mentorship Lee has provided, especially to the many Two-Spirit, Indigenous, and other LGBTQ+ students at UofT and in the wider community, SDS also wanted to celebrate her work—both literary and activist—in challenging colonial norms of gender and sexuality, and furthering the understanding of Indigenous women’s lives, experiences, and sexualities. It was especially rewarding to hear the other recipients (and the Two-Spirit leaders in the community who presented at the symposium we had organized earlier in the day) acknowledge they were proud to be recognized alongside Lee.

When the Bonham Centre hosted the World Pride 2014 Human Rights Conference at UofT, bringing together over 600 delegates from over 40 countries, at the opening event at Hart House organized by the Sexual and Gender Diversity Office before the annual Pride Pub, we were honoured to have Lee do the opening blessing and welcome, explaining what the land acknowledgement meant, which was a powerful and inclusive invitation to the diverse audience, many of whom were unfamiliar with the history of the spaces we now inhabit.

The New York Times November 14 obituary for Lee reads: “Lee Maracle, Combative Indigenous Author, Dies at 71.” In addition to the many errors and inaccuracies in the piece, to call Lee “combative” (the OED synonyms for which are “pugnacious,” “aggressive,” “antagonistic,” “quarrelsome”) not only reinforces the troubling legacy of how Indigenous peoples have often been represented, and used as justification for the systemic discrimination and violence perpetrated against them, but also the derogatory ways in which women who assert themselves are often characterized. More importantly, such a summing up belies what many of us who knew and worked with Lee would say was most notable about her: her generosity, her patience, her guidance, and her inclusive way of dealing with people, from the ignorant to the well-meaning. Some found Lee intimidating because it was hard not be aware of how much integrity and honesty there was to her presence. She was always direct, but never silenced nor was disrespectful of others, no matter how strongly she may have disagreed with them, which she would express, but never to wound or in the form of an attack—a “militaristic” quality she attributed to and challenged as colonial in the work of many male writers. Lee was amazingly generous in spirit and with her time, as evidenced by her prodigous service to the University of Toronto and her willingness to participate in the many activities and events she was asked to be a part of, including acting as advisor to UofT’s Truth and Reconciliation Steering Committee as they put together their final report and its 34 calls to action.

When asked by Carol Off in a 2019 interview on CBC’s As It Happens about her thoughts on reconciliation, she said that before there could be reconciliation, those 94 calls to action (put forward by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada in 2015) needed to be met. And that Canadians and the Government of Canada need to do that first. Only then could there be talk of reconciliation. When Off later asked her how she became so “worldly-wise,” Lee said it came from learning to listen to her Elders. Lee was a patient and perceptive listener—to stories, to testimonies, to the opinions and experiences of others, which is also what made her such a gifted and well-loved teacher. Above all, Lee was committed to the power of education to persuade and enlighten, recognizing how much more could be done to engage others and facilitate meaningful dialogue and understanding.

And finally, no tribute to Lee would be complete without mentioning her laugh and the role laughter and humour have played in her work and in her public speaking. As Carol Off pointed out in that same interview, “Humor is very important—your laugh, of course, which makes everyone laugh along with you—but humor is a big part of your work, isn’t it? Despite the darkness of these stories,” to which Lee responded:

“I want to get through it and get past it, and humour is like a push. When you want to sit down, humour stands you up and pushes you forward so that you can get through it; and we can’t get through it by dodging the dark. That’s like having no night. You have to have a night. So getting through the dark you need that motivating force, which is a little bit of a push every now and then, and that’s what humor serves in all of our stories.”

She left us too early, but we are grateful Lee Maracle has given us such a rich body of work—written texts and many recordings of lectures, interviews and conversations—so that she will continue to teach, and push, and we can continue to listen, learn and laugh with her.

–Scott Rayter, Associate Professor, Teaching Stream, Mark S. Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies and the Department of English