Featuring TL Cowan and Shana Ye, 2022-23 QTRL Faculty Fellows

T.L. Cowan and Shana Ye are not typical academics. From exploring how trans-feminist and queer methods fit into the world of scholarship to creating a fictional future where a Chinese-American empire exploits LGBTQ experiences, they offer unique perspectives in queer, trans, and sexuality studies.

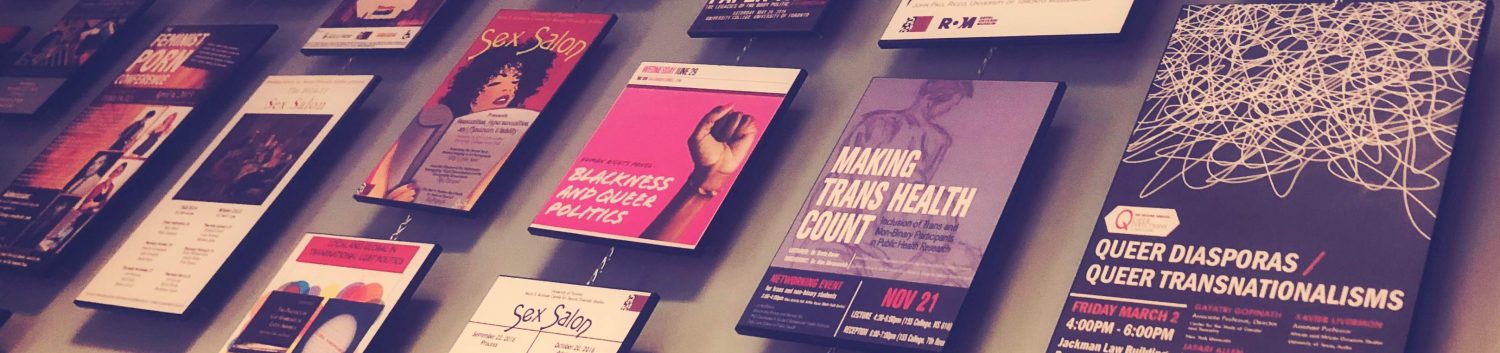

Cowan and Ye are this year’s Martha LA McCain Faculty Research Fellows at the Queer and Trans Research Lab (QTRL). Now in its second year, the QTRL, part of the Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies, aims to break down barriers between disciplines, between institutions and queer and BIPOC communities, and between artists, activists, and scholars.

Ye finds it invigorating to be in a setting where she doesn’t have to constantly explain herself.

“Lots of times I find myself needing to justify my work,” she says. “Here, my approach and baseline theoretical understanding is taken for granted. People are here to listen and be supportive.”

T.L. Cowan

Now an Assistant Professor of media studies in the Department of Arts, Culture and Media (UTSC) and the Faculty of Information, Cowan’s own early experiences of university have made her highly sympathetic to her students.

“It took me 10 years to do my undergrad,” she says. “I thought of university as an escape from a conservative, religious family in a very small town. Once I got to university, I was like: plan completed. But I didn’t really understand how to succeed at university, and I ended up on academic probation.”

Cowan moved to Vancouver and tried to go back to school, but dropped out again, this time to become a spoken-word and performance artist, and a queer cabaret performer.

“After five years, I got back into school,” she says. “I had to explain the traumatic process of coming out and my struggle with mental health to get the bad marks off my transcript. With the help of amazing administrators and feminist faculty, I got a do-over. When I went back to school, I absolutely loved it.”

Cowan got her Masters and PhD from the University of Alberta, where she plunged into Edmonton’s arts scene. She became part of the artist-run centre Latitude 53, edited a journal of visual culture, and “further developed my chops as an artist.”

Those early academic struggles and surviving what she calls an “extremely anti-feminist, homophobic home life,” has made Cowan determined to offer students the same support she was able to find.

“Being disowned was not a great experience, and I still have a lot of students who go through that,” she says. “When a student makes themselves known to me, I do everything I can to help.”

Cowan is currently exploring trans-feminist and queer media practices, especially in the digital realm. She studies cabaret as a performance practice, but also as a form of consciousness and “as a way of thinking about research through cabaret methodologies.” She is currently working on a book about cabaret methods, which, she says, the QTRL is already putting into action.

“Being able to work in a lab with community organizers and artists, as well as students and faculty—this is the cabaret method of distributed expertise,” she says. “It offers a built-in community to develop our work.”

Cowan is also finishing, with co-author Jas Rault, a book about “accountable ways for working trans-feminist and queer community practices into research methods.” Heavy Processing will be published in 2023 with Punctum Books.

Based on her experience with Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Cowan will spend her year with the QTRL exploring how cognitive disorders are treated in academic settings through a project called “Assisted Living in the Life of the Mind: Building Trans-Feminist & Queer Mental Health and Accessibility Networks in the University.”

“It’s not expected of a professor to have any cognitive disability,” she says. “Professors are supposed to be smart. Cognitive disorders are supposed to be for people who are not smart. In this context, coming out as somebody with a cognitive disorder as a faculty member is similar to coming out as queer in a conservative family.”

In the end, Cowan thinks her bumpy path to academic success has made her a better professor, because she doesn’t take it for granted.

“Rather than thinking of it as series of hoops to jump through, I think of it as a bunch of trails I’ve walked down.”

Shana Ye

Shana Ye jokes that reading in the bathroom while growing up in China helped her get where she is today.

“I would buy books on homosexuality and leave them on the toilet,” she says. “My father would read those books as well, and then would put some books he found interesting on top of the toilet. It was my first homosexual library.”

Ye says her family was always supportive.

“The normal narrative is that queerness is being oppressed in China,” she says. “That was not my case. The idea running through my family was that people are born equal. My family had seen so-called homosexuals and how they were mistreated, and they were very sympathetic and also empathetic.”

After obtaining a degree in International Relations in China, Ye attended the University of Cincinnati in 2002 as part of an exchange program, where she majored in Physics and Women and Gender Studies.

“At the time, the majority of Chinese students studied somewhat more conventional disciplines,” she says. “I was only the fourth person from China who got a degree in Women and Gender Studies. I was intellectually curious, and I was struck by how queer theory, post-modernism, and post-structuralism overlap with physics.” “Plus,” she laughed, “I was pretty bad at mathematics. I shamed the whole nation.”

Ye got her Masters in Women and Gender Studies at Cincinnati, before completing her PhD at the University of Minnesota. Her thesis was entitled “Red Father, Pink Son: Queer Socialism and Post-socialist Queer Critiques.”

“There was a lot of material in China about ‘sodomites’ in the 80s and 90s,” she says. “Dad read them before I even touched them.”

Ye had spent a year in Vancouver as a graduate student in 2008, but left determined never to return.

“I was paid so little, I absolutely hated Canada,” she says. “But everything is fate, and when I applied for a position, U of T was the first university to give me a full interview.”

Now an assistant professor of Women and Gender Studies at U of T, Scarborough, Ye is turning her thesis into a fictional work called Red Father, Pink Son: A Queer Journal to Chimerica.

“It’s a speculative history, set in the near future,” she says. “China and America merge into one empire. The empire requires queer people to confess their experience of being oppressed, but the real purpose is to assimilate them.”

Ye has found writing fiction to be freeing.

“I see myself as very creative,” she says. “I used to write a lot in Chinese, but somehow that ability was lost. Then, when I was converting my thesis to a book in 2018, I was stuck. Suddenly, I started writing in Chinese, just random thoughts, and I saw my identity as a creative writer again. Good writing creates space, creates imagination. Academia, ironically, can limit that kind of imagination.”

Teaching in Scarborough, where many students are South Asian or Southeast Asian, Ye has tried to avoid hierarchies and explore diverse cultural views.

“The student population in Scarborough means engaging different views of sexuality, and of how it intersects with both race and family.”

She hopes the QTRL will allow her to further overcome barriers between creative and scholarly work.

“We have faculty, artists, activists, undergrads, graduate students all hanging out,” she says. “We’re trying to break down the hierarchy.”

“I have multiple identities beyond the professor persona,” she says. “What I do the best is research work, but I want to be seen as a writer, an artist and a person who does parkour.”