By tearing down harmful conventions, Teiya Kasahara 笠原 貞野 is transforming the opera world

Photo credit: Eric Moniz.

See the original article on the Faculty of Arts & Science News Page, written by Cynthia Macdonald.

Opera is considered by many to be the most powerful of art forms. With its signature blend of music, art and theatre, it has been taking audiences on journeys to the deepest reaches of their souls for more than 300 years.

But opera has serious problems, too. Its canon is rife with storylines that are racist, sexist and offensive in other ways; its history has been beset by harmful casting and staging decisions. Opera is also governed by a rigid system of vocal classification that has created problems for developing singers, even affecting how they view themselves offstage.

This tension — between upholding opera’s power and beauty on the one hand, and radically changing it on the other — is what motivates Teiya Kasahara 笠原 貞野. Described as a “force of nature” by the Toronto Star, this queer, trans, mixed-race, non-binary performer is bringing opera to a whole new generation by reimagining beloved classics. And by creating new work that doesn’t just push boundaries, so much as it destroys them.

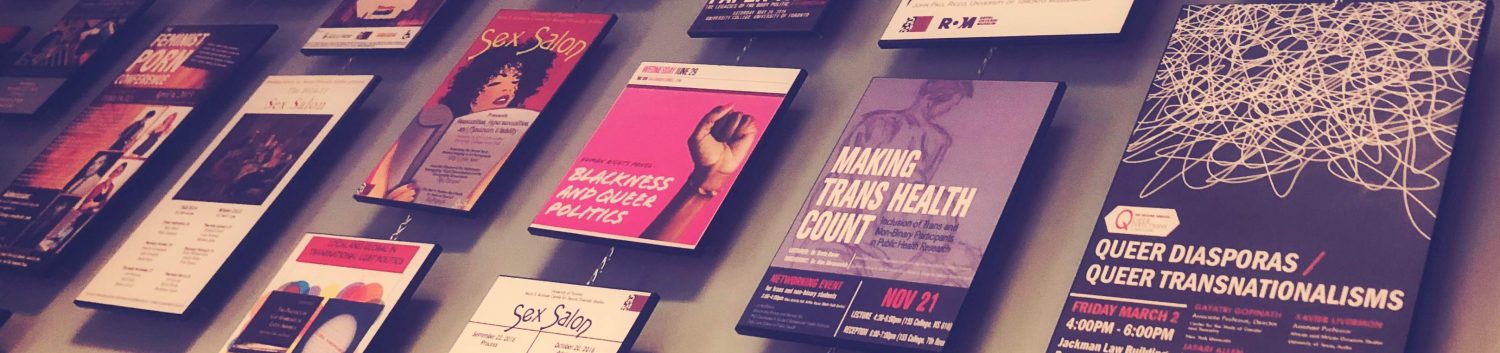

As June ends, Kasahara is finishing their term as Artist-in-Residence at the Mark S. Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies. The position supports artists whose work centres on LGBTQ2S+ lives, communities, histories and cultures, and expressly concentrates on the relationship between art, activism and social justice.

In addition to sharing their life experience with students and learning from other scholars, Kasahara has been developing a show that recently saw its first public workshop. Entitled Little Mis(s)gender, the project was inspired by the rigidly-gendered Mr. Men and Little Miss series of children’s books by Roger Hargreaves.

“The show deals with the notion of how we are subtly prescribed gender attributes, and how that is very binary for children,” Kasahara says. “And also how that relates to my experience as an opera singer — growing up and training in institutions where this voice categorization system, known as the Fach system, is very much used in how teachers teach, how directors cast, and how you’re seen in the industry.”

While they were still a teenager, Kasahara’s teachers deemed them to be a lyric coloratura soprano. This high, agile voice type is exemplified by trills, runs and acrobatics; in fact, lyric coloraturas have been called the “show-offs” of the opera world.

And yet coming into their late twenties, the singer realized that performing roles traditionally written for lyric coloratura voices just didn’t feel right.

To that point, they say, “I didn’t know I was queer or different, because I was so heavily focused on fitting in. On whitewashing myself, straightwashing myself. And just fitting into that voice type that I had: that feminine, bubbly, positive and light character I’d be playing, with few exceptions. In order to succeed as a singer professionally, I really trained myself to embody this persona that would fit in the industry.”

Having trained in university, performed as a member of the Canadian Opera Company’s Ensemble Studio, and sung traditional roles all over the world, Kasahara decided to take a break. They started exploring new and long-buried skills such as writing, acting, Japanese taiko drumming and athletics.

“I struggled for five or six years,” they say, “knowing that I needed to be queer: to feel seen and safe, and not have to hide myself.”

Some five years ago, Kasahara developed their signature show at Toronto’s Buddies in Bad Times Theatre. Called The Queen In Me, it centres and refashions a key character in Mozart’s The Magic Flute — one who is only onstage for some 12 minutes, but who famously sings a series of fast staccato notes before reaching one of the highest notes ever written for a singer: a high F above high C.

“The queen stops the opera mid-show, and starts to rail against oppression in the industry,” Kasahara says. “The show has kind of opened up a Pandora’s box for me — to be able to express my struggles, but also to reclaim them, heal them, and find catharsis for myself. And hopefully, for others as well.”

Since then, the multidisciplinary artist has been ceaselessly innovating. In 2021, the company they co-founded, Amplified Opera, was selected as the Canadian Opera Company’s first participant in its Disruptor-in-Residence program. It’s a program designed to support increased equity, diversity and inclusivity through activities that foster community engagement.

And outside of work, Kasahara has been entertaining the community in other ways — notably as “the Balcony Soprano” at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“On about March 13 of 2020,” they recall, “everything collapsed. I wanted to do something that would uplift me as well as sharing with others.” They initially led their co-op of artists’ condos in a karaoke singalong, which gave way to solo singing.

“I started singing and people loved it: they would stop walking their dog and look up. I ended up doing every performance twice, so people wouldn’t miss it.”

It’s but one example of the ways in which Kasahara takes hold of a difficult problem, and doesn’t let go until it’s solved.

“I love opera,” they state firmly. “I love to sing it, to hear it, to witness it. We have such a rich and glorious canon of music to draw from. And at the same time, opera can be misogynistic, homophobic, transphobic and racist: all of these things.

“One of my biggest passions is to re-examine that canon and see how we can engage with this art in a careful, thoughtful way. To advocate for more resources and opportunities to create new work. And, most importantly, to harm and hurt less in the future.”