Interview with Martha LA McCain Postdoctoral Fellow Sara Shroff

- Please tell us a little bit about yourself and your research project!

As a queer feminist with Kenyan, Indian, and Pakistani roots, the question of ‘self’ is a knotty one. I was born in Karachi and have called Karachi, London, Singapore, Atlanta, Washington, D.C., Nairobi and, most recently, New York City, home. This past summer I moved to Toronto from Brooklyn and am slowly learning the city and being schooled in its complex histories. My move to Toronto also marks a reunion with my beautiful mother from whom I have lived away from since I was a teenager, thus making Toronto an even more bittersweet homecoming.

I started my doctoral program in 2013 and am relatively new to academia. My professional life began in the non-profit and corporate sector two decades ago in philanthropy consulting, non-profit management, global development, fundraising, and finance. As an emerging transnational sexuality studies scholar, I take up some of these themes of economic development, financialization, global funding flows and new formations of capital in my work. My doctoral work especially takes up the genealogies of sexuality, governance, and economics in contemporary South Asia and its diasporas. I completed my PhD this past spring from the New School in NYC in Urban and Public Policy. My dissertation titled “Valuefacturing Life: Capital Encounters and Trans/Feminist CoBecomings in Pakistan and Beyond” examines three entangled sites — Pakistani working women’s fashion, gendered entrepreneurship and philanthrocapitalism, and khwajasira and transgender policy and community-based activism. Analyzing new formations of citizenship in Pakistan has helped me lay the groundwork for my second project which will be the focus of this fellowship. The project is tentatively titled “Dastaan-e-Qurbat: Queer Intimacies, Ethnicity, and Experiments in Living”. Qurbat is a South Asia/Arabic term which translates broadly to nearness, closeness, proximities, and intimacies. Dastaan is a Persian/South Asian term which means aural and aesthetic stories, such as epics, folklore, and mythology. My project traces four affective theoretical routes: brown femme lesbian diasporic sexualities; sex work and techno-promiscuities; trans religious/sacred regionalisms; and global south trans/feminist activism. As a scholar interested in the relations between queerness and the quotidian, affect and agency, language and world-making, I position qurbatein as an feminist intellectual practice to get at the intimate convergences and complicities of sexuality, pleasure, pain, power within the context of global South trans/feminisms and solidarities.

- As the first recipient of the Martha LA McCain postdoctoral fellowship, what aspects of the fellowship are you particularly excited about?

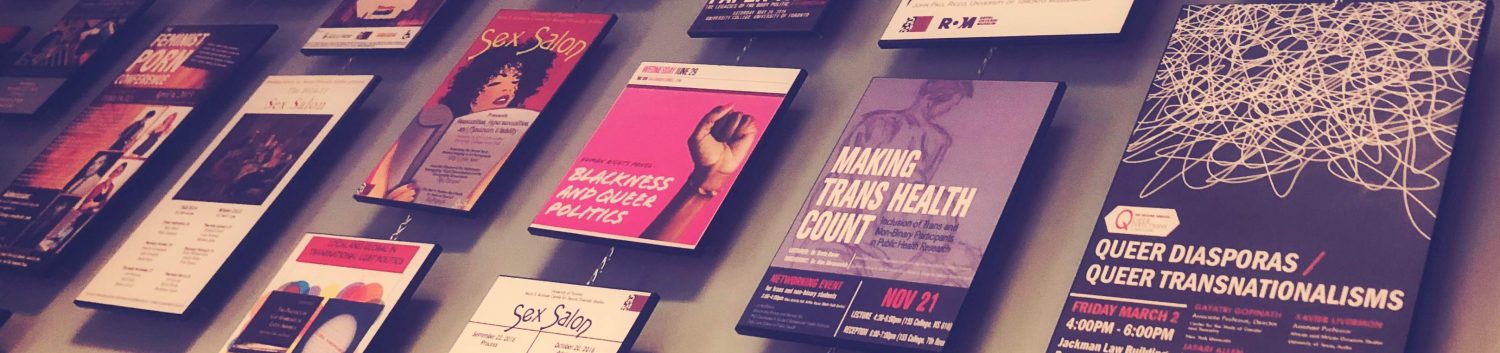

It is humbling to be a recipient of the first Martha LA McCain postdoctoral fellowship. I want to recognize that this reward is a collective labor of so many without whose love, radical pedagogy, and theories of resistance I would not have reached this point. I am excited about the fellowship because it gives first-generation PhDs and emerging scholars like myself the precious gift of funding which allows time for doing the work of thinking, studying, theorizing, listening, collaborating, and writing. Moreover, this fellowship enables me to access institutional resources, including archives, that are so important for an interdisciplinary transnational study of sexuality. I admire the politics of this fellowship and the Center as it one of the few so boldly vested in taking up sexuality studies as a serious mode of inquiry into transnational processes — imperialism, anti-Blackness, neoliberalism, xenophobia, homonationalism, and postcolonial nation making. By paying special attention to transnational feminisms, queer of color critiques, indigenous feminisms, and global south sexualities, the fellowship creates a space for scholars like me to take up divergent and complicated histories, practices, and politics of sexualities. I am particularly excited about being in conversation with the community of scholars and esteemed mentors at the Mark S. Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies, the Women & Gender Studies Institute, as well as scholars, activists, writers, poets, and artists in the greater Toronto area. However, most importantly my excitement is not about individual achievement and individualized research. Rather, my presence marks the Center’s commitment to creating infrastructural space and critical and communal support for emerging scholars to work on sexuality within a transnational frame.

- Your course will be an advanced seminar titled “Sexing South Asia,” and you touch on many aspects of society and culture in the course description. You mention studying South Asian sexual histories as a way to think about sexual rules, regulations and relationalities differently — what different perspectives will you be presenting in your teaching?

This course is informed by decades of activism and scholarship around sexuality in and from South Asia. It is equally inspired by almost a decade of conversations I have had with communities across South Asia and its diasporas about desires, fashion, law, borders, activism, care, identity documents, feminisms, and labor. In particular, this course takes up questions being raised by intergenerational work by and of feminist, queer and trans communities in multiple spaces about survival, pleasure, identity, resistance, pain, home, life, and belonging. My goals in this course are three-fold. First, we unsettle and disrupt assumptions of stability and coherence about the category of South Asia and South Asian. Second, we develop new analytics to understand sex, gender, and sexuality in ways that challenge dominant formations in area studies and postcolonial theory, as well as gender and sexuality, queer and trans studies. And third, we center transnational frames to understand and challenge how we think about home, diaspora, resistance, local, indigenous, and global in the context of sexualities and South Asia.

The main questions, therefore, that underpin this course are: What happens when we center South Asia to think about histories of sexualities, theories, and genealogies as we move across geopolitical and geographic boundaries? How do we think about hijra, khwajasira, moorat, sakhi, lesbian, Salaam Canada, SALGA, and desi drag? How do we analyze the Pakistan Transgender Protection Bill 2018, the decriminalization of same-sex in India, and other gender and sexuality policies in Bangaldesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka? How do we think about these demarcations and discourses sideways, side by side, and across borders? How do we account for anti-Blackness in South Asia and South Asian communities? How are frames of feminism shifting to include or exclude all women, queer, trans and gender non-conforming communities? What constitutes indigeneity and decolonization in these complex contexts? We will explore how bodies, desires, pleasures, practices, identities, labor, and affect are being mediated by the state, social media, sacredness, and transnational securitization by centering literature, poetry, policy, visual culture, economics, religion, and law.

- Why is it important to explore this subject with undergraduates, and what do you hope students come away with through their experiences in the course?

This course is important for undergraduates because all of our understandings of sexualities can be restricted by geography, geopolitics, popular culture, and our own historical readings of the world. These readings limit our imagination, that is, the ability to imagine different worlds and practice a world-making that is rooted in responsibility to each other, collective social justice, and reciprocity. I see teaching as a work of building learning communities that is attentive to multiple and mobile contexts, registers of time, histories, infrastructures, and most importantly, labor. The experience I have had teaching and often being taught by undergraduates in New York City and Karachi have solidified for me how sexuality permeates all sites of power, and how these technologies and sites are being questioned in classrooms by those we too often and too easily dismiss as youthful, immature, inarticulate, or inexperienced.

In centering my students I hope to co-create a learning community that allows us to ask the difficult and delicate questions that we are so often afraid to ask of ourselves, the theories that are taught to us, and the worlds we may be comfortable in. Asking such questions will require of us the ability to listen to and be accountable to each other, to vulnerable and marginalized people, to languages that are forgotten and erased, and histories that are invisiblized or subjugated, but still always present. We will learn how to historicize and locate multiple formations of sexuality, race, gender, language, and citizenship in different contexts, and the connections and movements between them. Ultimately, my hope is that the course centers South Asia and South Asian diasporic histories that are part of the quotidian, and which are crucial to how we queer and decolonize histories of sexualities.

- Hopefully you have had the chance to learn a little bit about the Centre and our mission. How do you think your work contributes to that?

My work contributes to the Centre’s mission of studying sexuality through an interdisciplinary lens. The Centre emphasizes that sexuality — formed along the intersections of race, class, gender, religion, ethnicity, disability, and citizenship — is a technology of power that determines the value of different lives, and who is defined as human and therefore valuable in the first place. My dissertation and my newer work attend precisely to how sexuality is a formation and mechanism of power to determine life, value, and death in South Asia and South Asian diasporas, across structural injustices and inequities in everyday life.

Canada is a major site for South Asian diasporas. As a new settler in Canada, a naturalized US citizen, and as a muhajir (migrant) in and from the port city of Karachi, I am committed to attend to violent processes of colonialism, transatlantic slavery, migration flows, and immigration politics. Given the multidisciplinarity of my work and its multiple locations, I am in conversation with scholars, artists, lawmakers, writers, performers, and poets across South Asia, Europe, Australia, Canada, and the US. These are the communities I am honored to be a part of and it is these collective knowledges from which we all benefit. I hope my presence at the Center will continue to foster critical and urgent conversations around sexualities transnationally that speak to collective solidarities, ancestral rage, and healing practices.